A lot has been written about Dante. Here is a brief biography of myself.

At age zero I was born in New York City. Two years later, my little sister was born, and we moved a block away, from one small Manhattan apartment into a slightly larger one. I have lived in that same apartment building since then.

Sometime in middle school, I learned about the Hero's Journey. The final step, having gone through trials and tribulations, is that the hero should return home, changed.

At age fourteen, (I know I was fourteen because that is how old I was when) the pandemic hit, and my mother got the idea that my younger sister and I should read the Odyssey, hoping to get her children off their screens and expose them to some culture. This did not really click for me. Even the best translations are dense to an unenthused high school freshman, and after all, I knew the ending already. An “odyssey” is a long mission, of course, but it is inherently a mission that gets completed.

At eighteen I went to college. One month in, I cried my eyes out and begged to make the bus trip to visit home for a weekend. Freshman year would go on to be a low point for my mental health for several reasons, but one highlight was taking Afterlives, a class that dedicated much of the curriculum to Dante’s Divine Comedy.

I almost did not return to college at nineteen, so it was at the last minute that I signed up for Dante and the Medieval World, because the professor was engaging and the topic seemed like something I could get well invested in (and I needed three more credits).

It was at this time that I started to develop a deep investment into the Divine Comedy. My interests have included Greek mythology since I was very small, but as I’d gotten older I had become increasingly invested in Christian theology as well-- the antiquated and adapted ideas of what was right and wrong, the idea of what forms of magic or artistic depiction had validity or didn't, the specific ways one could gain or lose power in Christian academic structures. I had briefly developed an interest in niche heresies over the summer. At the same time, I was getting really into Ultrakill, a first person shooter set in Dante's Inferno. Though Afterlives was interesting, that year had been a shitshow on a personal level, and besides, there had still been things in that class that were not the Divine Comedy. This class narrowed in on the topic.

What I am trying to say is, it was a perfect storm for me to become obsessed with the most unlikely interest I have ever had.

Suddenly, new worlds opened up. I was incredibly invested in someone I could not have had less in common with on a structural level (except perhaps genealogy in the same area: my mother is Greek. Three cheers for the Mediterranean) and yet, the world he built was like crack to an amateur theologian and an enjoyer of the classical tradition. Part of it was just how novel the world he crafted was– even seven hundred years later, the Comedy still felt new and interesting, because of how specific the points he was trying to convey were. And part of it was the narrator himself.

Many adaptations of Inferno have the protagonist fighting through hell. But Dante is not Doomguy. Dante is not only afraid for his immortal soul as a Christian, but literally afraid of the kind of horrors he is being put in front of. He passes out and wakes up in different locations, often. He weeps. He surrounds himself by brilliance: his guide through Inferno and Purgatory is another immortally famous writer, his divine inspiration and his guide through Paradise is, in all but specific phrasing, a saint. And yet, despite being the author, despite an occasional reference that makes it clear he thinks very highly of his own abilities as a writer and poet, he does not really put himself in competition with these people. It was that willing depiction that appealed Dante to me as a character. He seemed to agree with me that the human spirit may be indomitable, but not unmoving.

So it was halfway into this class that a throwaway line in a Youtube video caught my interest.

The video was riddled with minor inaccuracies (referring to Beatrice as Dante's "girlfriend" as opposed to more accurately his "crush”) but the throwaway line that got me was the idea that the whole of the Divine Comedy was Dante himself "coping with the psychological pain of his exile."

A matter of days after hearing that, we made it to that point in Paradise (Canto XV) where Dante meets his great-great-grandfather Cacciaguida, a Florentine himself, who disdains the modern Florence, referring to her as a woman who used to be young, pure, beautiful and virtuous, but had since lost herself to corruption and vice.

It was in that class that something actually clicked.

Here is where we must differentiate Dante, the author, and Dante, the character, who has traipsed through the Christian afterlife. Dante the author was living in either Verona or Ravenna at the time. But Dante the character was still living in Florence. Dante the traveller did not know he was going to be exiled. (Neither version knew that Dante would never go back home.)

It is in this way that we have to understand Cacciaguida’s words as that of Dante, the bitter author. Obviously, as his grandfather’s grandfather, Dante never actually met Cacciaguida. But that only makes the words he puts into Cacciaguida’s mouth all the more telling.

A brief segway about New Yorkers. There are two different kinds. The first is, in short, the Big-City Supremacist. This person may occasionally detail to you things that happen everywhere as if they could only possibly occur in New York City. John Updike synthesized this philosophy in a quote: “The true New Yorker secretly believes that people living anywhere else have to be, in some sense, kidding.”

The other kind is, I suppose, the Inferiorist. The person who complains incessantly, about the subway, about parades, about the cars or the shouting or the perpetually rising price of necessities. If they’re old-school enough, it’ll be about how New York City was better before X event or Y event. This event will usually coincide with something that happened to them on a personal level.

Most New Yorkers are both, depending on circumstance or topic. If you happen to meet one who falls solely into one category, disregard anything they are saying. The staunch Supremacist has not lived there long enough. The staunch Inferiorist would be better off moving.

Knowing this, we return to Cacciaguida, who stands in for the Inferiorist. In his day, Florence was “sober and chaste, and lived in tranquility.” Most importantly, in those good old days, people didn’t live in fear of fickle politics or financial ruin. A very attractive idea to an author who had been exiled from a much more modern Florence for his political beliefs followed by an inability to pay the fine pinned on him.

But something does not line up, even from the point of the disillusioned author. The opposite of love for something or someone is not hatred, it is indifference. And Dante is incredibly passionate about Florence, even almost twenty years after his exile. The resentment has had time to blossom in ways that precede the introduction of Cacciaguida. He starts Canto XXIV, in the midst of Fraud, with a scathing critique: “Be joyous, Florence, you are great indeed,/for over sea and land you beat your wings;/through every part of Hell your name extends!”

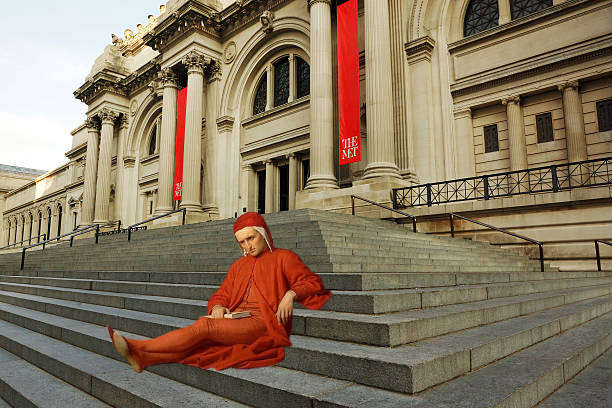

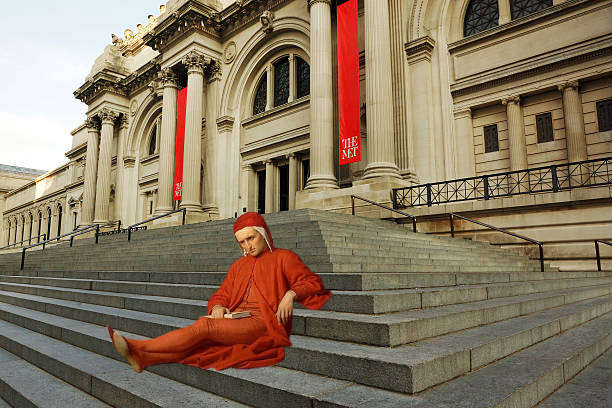

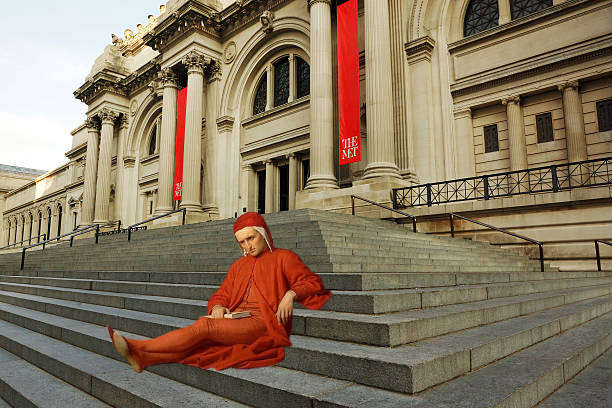

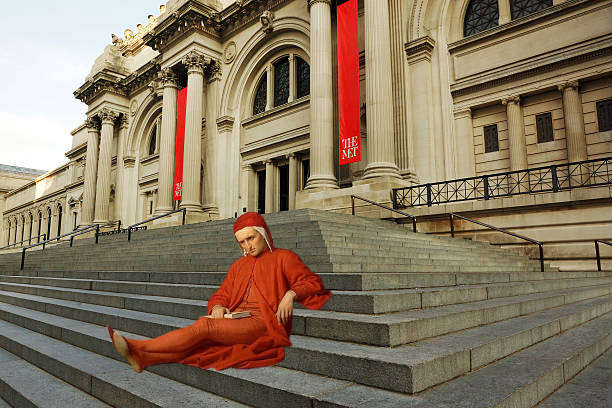

And yet, her name is also inextricable from the Divine Comedy, a piece of literature which Dante has already treated as the baring of his immortal soul. I was tasked with being the discussion leader for the class where we discussed Paradiso Canto XV. I did not do a very good job of it, but I did get to bring up that Dante’s persistent mentions of Florence were very reminiscent of being from New York City. By some statistical anomaly in Upstate New York, I was the only New Yorker here.

I laughed at the idea of Dante being an archetypal New Yorker. I contemplated, for a moment, the idea of never going to New York City again.

When I am eighteen years old, about one year and a couple months before this publication date, I lie on the floor and cry so hard I can't breathe.

This is one of the lowest points of my mental health. The rest of the school year will culminate in a slow creep upwards, but by the end of the year this memory alone will have me convinced that I do not want to come back to college the next year.

There is misery without any specific origin. I am in a good place. I am even in a room I have to myself. And I am two hundred miles away from home.

I'm not that far, really. I have met a transfer student who has come to Syracuse all the way from Italy. We’d talked about her plans to stay in town for winter break.

Ravenna, where Dante Alighieri dies, is only 65 miles from Florence. A determined traveller in good conditions can walk there in three days. It’s two hours by train. If you open his Wikipedia page, there is a section dedicated to "Exile from Florence". In spite of the fact that by 1315, his exile has been extended to his sons as well, “he still hoped late in life that he might be invited back to Florence on honorable terms”.

This is the absolute lowest point my mental health will be in the 2024-2025 school year, but at least I know I can go home.

Even contemplating the idea made me physically nauseous.